Endotracheal intubation using semi-rigid optical stylet in simulated difficult airways of high grade modified Cormack and Lehane laryngeal views

Article information

Abstract

Background:

Endotracheal intubation in patients with compromised cervical vertebrae and limited mouth opening is challenging, however, there are still limited options available. Among devices used for managing difficult airways, the Clarus Video System (CVS) might have considerable promise due to its semi-rigid tip. We evaluated the performance of CVS in patients with simulated difficult airways.

Methods:

Philadelphia cervical collars were applied to 74 patients undergoing general anesthesia. The degree of simulated difficult airway was assessed by observing laryngeal view using McCoy laryngoscope; modified Cormack and Lehane grade (MCL) ≥ 3a (high-grade group, n = 38) or ≤ 2b (low-grade group, n = 36). Subsequently, patients were intubated using CVS by a blinded practitioner. We evaluated total time to intubation, intubation success rate, and conditions of intubation.

Results:

Intubation took significantly longer time for the high-grade group than that for the low-grade group (38.2 ± 25.9 seconds vs. 27.9 ± 6.2 seconds, time difference 10.3 seconds, 95% confidence interval: 1.4–19.2 seconds, P < 0.001). However, CVS provided similar high intubation success rates for both groups (97.4% for the high-grade and 100% for the low-grade group). During intubation, visualization of vocal cords and advancement into the glottis for the high-grade group were significantly more difficult than those for the low-grade group.

Conclusions:

Although intubation took longer for patients with higher MCL laryngeal view grade, CVS provided high intubation success rate for patients with severely restricted neck motion and mouth opening regardless of its MCL laryngeal view grade.

INTRODUCTION

Endotracheal intubation in patients with difficult airway remains a challenging issue for physicians. Although various devices have been developed to manage a variety of airway situations, limited options are available for patients with restricted neck motion and mouth opening [1,2]. Because of their bulky blades, conventional laryngoscopes and video laryngoscopes have limited maneuverability and may cause dental or mucosal damage. Although there are several alternatives to conventional laryngoscope such as gum-elastic bougie or lighted stylet, that can facilitate tracheal intubation, they could only result in ‘blind intubation’ in most cases [1]. Fiberoptic intubation, the current gold standard for difficult airway management, has shown to be time-consuming. Moreover, considerable learning time is required for its use in clinical practice [2,3].

The Clarus Video System (CVS; Clarus Medical, USA) is a semi-rigid optical stylet equipped with an adjustable on-board monitor and a re-chargeable battery (Fig. 1). Because CVS requires neither sniffing position nor neck flexion and atlanto-occipital joint extension, this device appears to be particularly suitable for patients with limited neck motion and mouth opening. Therefore, the objective of the current study was to evaluate the intubation success rate and intubating conditions of CVS in simulated difficult airway situation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board of the Asan Medical Center (IRB no. 2010-0765). Written informed consent was obtained from each participating patient. We recruited consecutive patients aged 20–70 years with an American Society of Anesthesiology physical status classification I or II who were scheduled for elective surgery under general anesthesia. Exclusion criteria were: an anticipated difficult airway (Mallampati class 4, thyromental distance < 6 cm, or inter-incisor distance < 4 cm), body mass index > 30 kg/m2, loose tooth, and any pathology of the face, oropharynx, or larynx that might deteriorate upper airway patency.

Standard monitoring techniques including electrocardiography, non-invasive blood pressure, and pulse oximetry were applied. All patients were treated with glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg intravenously to decrease salivary secretion. Modified Mallampati class and maximal inter-incisor distance were recorded prior to anesthetic induction. Following pre-oxygenation of lungs with 100% oxygen for 3 minutes, anesthesia was induced with propofol 2 mg/kg and sevoflurane 7 vol%. After mask ventilation was secured, rocuronium 1 mg/kg was administered intravenously and full neuromuscular blockage was confirmed with a nerve stimulator by train-of-four.

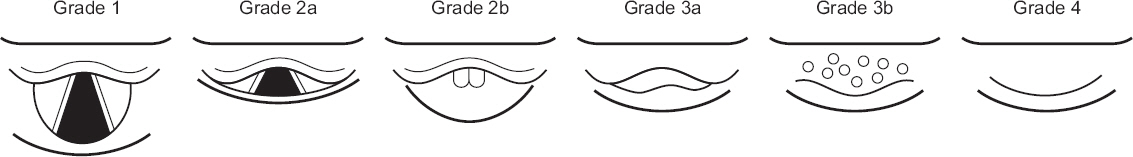

To limit extension of the neck and opening of the mouth, an appropriate-sized rigid Philadelphia cervical collar (Philadelphia Cervical Collar Co., USA) was applied after removing the pillow and inter-incisor distance was measured again. Laryngeal views in both Macintosh and McCoy configurations were evaluated with a McCoy size 3 laryngoscope [4]. Laryngoscope was performed initially in Macintosh configuration without activation of the hinged tip followed by activation of the distal tip with compression of the lever (McCoy configuration). Those laryngeal views were graded according to the modified Cormack and Lehane (MCL) classification (Fig. 2) [5]. According to the laryngeal view with McCoy configuration, all patients were classified into either high-grade group (MCL grade ≥ 3a) or low-grade (MCL grade ≤ 2b).

A graphical illustration showing laryngeal views classified by the modified Cormack and Lehane (MCL) grade. MCL grades are as follows: Grade 1, entire glottis visible; Grade 2a, glottis partially visible; Grade 2b, only arytenoid cartilages visible; Grade 3a, only epiglottis visible and can be lifted; Grade 3b, only epiglottis visible but cannot be lifted; and Grade 4, neither glottis nor epiglottis visible. In our study, we classified patients into either high-grade (MCL grade ≥ 3a) or low-grade (MCL grade ≤ 2b) according to the laryngeal view with McCoy configuration.

After mask ventilation was restarted with 100% oxygen and sevoflurane for 60 seconds, endotracheal intubation was attempted using the CVS by a single experienced operator who was blind to the result of the patient’s MCL grade. The CVS was inserted into the mouth with a preloaded endotracheal tube (7.0 mm ID for women and 7.5 mm for men). For this study, we constructed a malleable stylet curved 70 degrees a few centimeters from its distal. To minimize direct contact of the optical lens with oropharyngeal mucosa and secretions, the tracheal tube was adjusted so that its distal end would be just beyond the tip of the stylet, covering about one third of the monitor screen. The operator held the stylet and tracheal tube in the right hand and used the left hand to open the patients’ mouth and pull the mandible forward. To facilitate the advancement of the endotracheal tube into the oral cavity, the operator’s left thumb pressed the tongue simultaneously (single-handed chin lift maneuver). If epiglottis was seen, the tip of the CVS was threaded under the epiglottis. Under direct visualization of vocal cords, the tip of the CVS was carefully advanced until tracheal rings were seen and the tracheal tube was slid into the trachea. Each attempt was stopped if the time exceeded 180 seconds or if arterial desaturation occurred (SpO2 < 90%) before endotracheal intubation was accomplished [6]. Endotracheal intubation was deemed a failure if it could not be accomplished within two attempts. If endotracheal intubation failed in this way, the reason for the failure was noted and the airway was managed with an appropriate method by an attending anesthesiologist. The intubation time was defined as the time from the insertion of the tip of the CVS into the patient’s mouth until confirming the position of the endotracheal tube by capnography. Intubation conditions for the CVS were graded as excellent, good, fair, or poor with regard to insertion into the oropharynx, visualization of the epiglottis, placing the tip under the epiglottis, finding the vocal cords, advancement into the glottic aperture, and the maneuverability of the endotracheal tube. Overall ease of tracheal intubation was reported using a verbal rating scale (VRS) with a score of 0 to 10 (0 = extremely easy; 10 = impossible). Any complication such as oral mucosal injury, lip laceration, or dental trauma was recorded.

Statistical analysis

Our primary outcomes were endotracheal intubation time. In our preliminary study conducted in 10 patients with restricted neck motion and mouth opening, standard deviation (SD) for intubation time using the CVS was 14.8 seconds. At least 36 patients per each group were required to detect a difference in mean intubation time of 10 seconds with an alpha error of 0.05 and a power of 0.8. All data are presented as mean ± SD or number (%) of patients. Normal distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For group comparison of patients’ characteristics such as age, weight, height, thyromental distance, sternomental distance, and mouth opening distance before/after applying cervical collar, t-test was used for age, weight, height, thyromental distance, sternomental distance, and mouth opening distance before/after applying cervical collar. Patients characteristics including sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification, modified Mallampati classification, and MCL laryngeal view grade in Macintosh/McCoy configuration were compared using Pearson’s chi-square test. Fisher’s exact test or chi-square test was used for comparison of success rate at the first intubation attempt between groups. All statistical data were analyzed using SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corp., USA) and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 74 patients were enrolled in this study (high-grade [MCL grade ≥ 3a, n = 38], low-grade [MCL grade ≤ 2b, n = 36]). Demographic data and airway characteristics of patients in the two groups are summarized in Table 1.

Activation of hinged tip (McCoy configuration) improved laryngeal view in 36/74 (48.6%) patients. Among four patients with MCL grade 2b in Macintosh configuration, McCoy configuration improved laryngeal view to MCL grade 2a in all patients. Of 50 patients with MCL grade 3a in Macintosh configuration, 32/50 (64.0%) patients were downgraded to MCL grade 2a (5 patients) or grade 2b (27 patients) after applying McCoy configuration. However, in two patients with MCL grade 3b in Macintosh configuration, laryngeal view did not improve with McCoy configuration.

The intubation time of the high-grade group was 36.9% longer than that of the low-grade group (38.2 ± 25.9 seconds vs. 27.9 ± 6.2 seconds, time difference of 10.3 seconds, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.4–19.2 seconds, P < 0.001, Table 1). Overall ease of intubation in the high-grade group was more difficult than that in the low-grade group (4.2 ± 1.7 vs. 2.9 ± 1.1, difference of 1.2, 95% CI: 0.6–1.9, P < 0.001). Intubation conditions of the CVS were not significantly different between the two groups with regard to insertion into the oropharynx, visualization of the epiglottis, getting the scope under the epiglottis, or maneuverability of the trachea tube. However, visualization of vocal cords (P = 0.040) and advancement into the glottic aperture (P = 0.014) were more difficult for the high-grade group than those for the low-grade group (Table 2).

In the high-grade group, overall intubation success rate and intubation success rate at first attempt were 97.4% and 94.7%, respectively. In the low-grade group, all patients were intubated at the first attempt. In two patients of the high-grade group, first intubations failed due to secretions interfering visual fields. Second intubation was performed successfully in one patient after suction of the secretion. However, in the other patient, the epiglottis could not be found with the CVS at the second attempt. Therefore, intubation was not performed (Table 2).

There was no mucosal or dental damage in either group. However, there were two minor lower lip lacerations during CVS manipulation in the low-grade group. No episode of desaturation was observed during the study.

DISCUSSION

Intubations time took 37% longer in the high-grade group than that in the low-grade group. However, the CVS offered a high intubation success rate (> 98%) under difficult airway situation simulated by a rigid Philadelphia cervical collar. Even when patients showed severely restricted laryngeal views which could not be improved by the McCoy configuration (high-grade group), the CVS consistently offered a high intubation success rate of 97.4%.

Although various types of optical stylets have been made for managing difficult airway situations, the CVS is particularly useful because of its malleable semi-rigid tip. The semi-rigid tip of the CVS has both adjustability and stiffness. When using a conventional rigid optical stylet, the fixed angle of the tip makes it difficult to negotiate the oral-pharyngeal-tracheal axes in patients with limited neck motion and mouth opening. In contrast, adjustability of the tip of the CVS may help increase the chance of successful endotracheal intubation in such patients [7]. The practitioner can adjust the angle of the malleable tip to suit the patient’s neck anatomy prior to intubation attempt. Thus, neck extension is scarcely needed during this procedure [8]. Moreover, even when the first intubation attempt fails, the tip of the CVS can be re-adjusted to the patient’s oral-pharyngeal-tracheal axes in the light of the previous intubation attempt [9], although we fixed malleable stylet to be curved 70 degrees in the current study.

Although a previous study has demonstrated a high intubation success rate (> 90%) using the CVS in a simulated difficult airway situation with a cervical collar [7], the degree of simulated difficulty is not properly assessed. Applying the cervical collar is a widely used method for simulating a difficult airway situation. However, this method only produces a predicted difficult airway [1]. Because not all simulated difficult airways represent a ‘true’ difficult airway, intubation success rate could be overestimated without validating the effect of the cervical collar [10]. Also, the degree of application of the cervical collar may differ among practitioners and patients [11]. Such uncertainty and heterogeneity in simulating a difficult airway situation may make it difficult to evaluate and compare the performance of alternative airway devices [12]. In the current study, the actual laryngeal view was assessed in all patients with application of a cervical collar using McCoy laryngoscope. It is known that MCL grade of a simulated difficult airway varies from grade 1 to grade 4 [4,10,13]. In our present study, the MCL grade with Macintosh configuration varied from grade 2b to grade 4 and the majority of patients were at grade 3. Because most patients with MCL grade 3 could be simply intubated using conventional laryngoscopes with a simple adjunct or external laryngeal maneuver [1], we applied McCoy configuration to sort out patients with a more difficult airway. McCoy laryngoscope with activated hinged tip is known to improve laryngeal views in patients whose necks are limited with cervical collars by lifting the epiglottis. Thus, we used this laryngoscope to distinguish patients with true difficult airways whose laryngeal views were not improved in spite of McCoy configuration. As a result, 32 patients (47.1%) out of 68 MCL grade 3 cases with Macintosh configuration were downgraded to grade 2a or 2b after application of McCoy configuration. These patients were included in the low-grade group (MCL grade ≤ 2b) while the remaining 34 patients in whom glottic structures were not visible (MCL grade ≥ 3a) were assigned to the high-grade group.

In our study, intubation time took significantly longer for the high-grade group of simulated difficult airways, although we used CVS. There were some difficulties during the course of intubation in the high-grade group. The VRS for the overall easiness was higher. Specifically, visualization of vocal cords and insertion of the scope into the glottic aperture were more difficult significantly. In these cases, the epiglottis was closely located to the posterior pharyngeal wall. Therefore, the semi-rigid tip of the CVS was used to lift the epiglottis against the resistance of the laryngeal wall. Such difficulties were suspected to be causes of the longer intubation time for the high grade group. However, CVS offered a similar high intubation success rate on the first attempt and in terms of overall attempts (94.7% and 97.4%, respectively) in both high- and low- grade groups. In the low-grade group, all patients were successfully intubated on the first attempt. In a review article by Mihai et al. [1], the intubation success rate on the first attempt in a difficult airway situation is approximately 92% when alternative intubation devices including a rigid optical stylet and video laryngoscope are used. Thus, our current findings with CVS seemed to be clinically acceptable considering these results from previous studies in both groups. Especially, in 17 patients with MCL grade 3b and grade 4, the CVS consistently showed high intubation success rate of 94.1%. Among 15 patients with MCL grade 3b with McCoy configuration, 14 patients were intubated at first attempt and the remaining one patient was intubated at the following attempt. Of two patients with MCL grade 4 and McCoy configuration, the intubation was successful at first attempt in one patient, although the other one could not be intubated at either attempt. Although intubation difficulty was increased in patients with MCL grades 3b and 4 [5], previous studies did not report intubation performance in patients with MCL grade 3b or 4 because such high grades of laryngeal views were not observed in those studies [10,13]. Thus, it is noticeable that our study showed acceptable intubation performance of the CVS in those with high grade laryngeal views.

The tip of the CVS also has sufficient strength, like other types of optical stylets with rigid tips. Owing to the stiffness of the tip, optical stylets have several advantages over a flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope which is the current gold standard for managing a difficult airway situation [14]. Even when a patient’s retropharyngeal space is limited, the semi-rigid tip of the CVS may advance against the resistance of the pharyngeal soft tissue [15]. Also, the tip of the CVS can lift up the epiglottis, even though there is no gap between the epiglottis and the retropharyngeal wall [16]. These features may provide better maneuverability and a steeper-learning curve than those of flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope [17].

In one case of the high-grade group, the epiglottis could not be found with the CVS. This was probably due to the almost absent hypopharyngeal space between the tongue and the posterior pharyngeal wall. Therefore, intubation was not progressed. We used single-handed chin lift maneuver to expand the retropharyngeal space without other external laryngeal manipulations. Lee et al. [18] have reported that BURP (backward, upward, and right-sided pressure) maneuver can worsen the laryngeal view than single-handed chin lift maneuver when using the CVS. They also reported that modified jaw thrust maneuver (two-handed aided by an assistant) was the most effective one in improving the laryngeal view and shortening the intubation time in normal patients. We did not use the modified jaw thrust maneuver because it needed a skilled assistant. In addition, its effectiveness seems to be limited in patients whose neck motion is restricted with cervical collar such as in our patients. In one patient in the high-grade group who failed to be intubated, the single-handed chin lift maneuver was not effective to make retropharyngeal space behind the tongue. However, the modified jaw thrust maneuver combined with tongue compression by the operator’s left thumb could be more effective in such a case, although it was not applied in this study.

In previous studies, limited view due to excessive secretion and tissue contact have been consistently reported as drawbacks that hinder successful endotracheal intubation using intubating stylets [17,19]. In our current study, two patients failed to be intubated at first attempts and the cause of the failure was visual interference due to excessive secretion. Therefore, previous or prompt oropharyngeal suction seems to be helpful in using the CVS.

Our current study has several limitations. First, our investigation was performed in patients with simulated difficult airway situation, not in cases with known history of difficult airway situation. It is almost impossible to conduct study in such patients. The main drawback of simulated difficult airway is the uncertainty of achieving ‘true’ difficult laryngeal view. Without validation, applying neck collar cannot guarantee ‘true’ difficult airway. In this point of view, our study had strength as all laryngeal views of simulated difficult airway were validated by examination with McCoy configuration. Second, adrenergic responses such as blood pressure and heart rate could not be evaluated because of prior laryngoscopic examination. To discriminate patients with more difficult airway, McCoy laryngoscopic examination was imperative. Finally, operator bias might be possible because all endotracheal intubations were performed by a single experienced operator who had done over 50 endotracheal intubations using the CVS. However, a single operator could have advantages as it could eliminate the bias from multiple operators with various levels of experience. Visual assessment of laryngeal view may also have observer bias. However, the result of laryngeal assessment was blinded to the CVS operator. Therefore, any potential bias was minimized by our study protocol.

In conclusion, although the intubation took longer for patients with higher MCL laryngeal view grade, the CVS provided high intubation success rate regardless of MCL laryngeal view grade in patients with difficult airway situation simulated by a Philadelphia cervical collar. We believe that the CVS system is a useful option for aiding endotracheal intubation in patients with severely restricted neck motion and mouth opening.