A comprehensive review of difficult airway management strategies for patient safety

Article information

Abstract

Difficult airway management is critical to ensuring patient safety. It involves addressing the challenges and failures that can occur, even with skilled healthcare providers, during face mask ventilation, intubation, supraglottic airway placement, invasive airway procedures, or extubation. Although the incidence of the most critical situation in airway management, “cannot intubate, cannot oxygenate,” is low at 0.0019–0.04%, its occurrence can have severe consequences, including dental injury, airway injury, hypoxic brain damage, and even death. This study aimed to offer healthcare providers a comprehensive and evidence-based approach for difficult airway management by reviewing recent guidelines and incorporating the latest evidence-based practices to improve their preparedness and competence in difficult airway management, and thus ultimately contribute to improved patient safety.

INTRODUCTION

Effective airway management involves addressing the challenges encountered in difficult airway situations and potential complications, ranging from aspiration and esophageal intubation to more severe outcomes, such as dental injury, hypoxic brain injury, and even death [1]. It requires a comprehensive approach that includes airway evaluation, preparation for difficult airway management, actual management of the difficult airway (both anticipated and unanticipated), and confirmation of tracheal intubation, extubation, and follow-up care [2].

To explore the latest insights and approaches to difficult airway management, this article aims to review various guidelines, with a focus on the 2022 American Society of Anesthesiologists and the 2015 Difficult Airway Society (DAS) guidelines. Considering multiple guidelines, this study aimed to provide healthcare providers with an up-to-date understanding of difficult airway management and recommended strategies.

INCIDENCE

The incidence rates of difficult and impossible face mask ventilation are 1.4–5.0% and 0.07–0.16%, respectively [3,4]. The incidence rates of difficulty and impossibility of intubation with a classic laryngoscope are 5–8% and 0.05–0.35%, respectively [5]. The success rate of intubation using a video laryngoscope ranges from 97.4% to 99.6% [6]. The incidence of impossibility of placing the supraglottic airway (SGA) ranges from 0.2% to 8% [7]. The incidence of situations “cannot intubate, cannot oxygenate” ranges from 0.0019% to 0.04% [7-9].

EVALUATION OF THE AIRWAY

Healthcare providers involved in airway management must be able to identify and assess risk factors for difficult airways. Predicting a difficult airway allows the implementation of prophylactic measures and provides valuable time for adequate preparation. Various predictive factors indicate the risk of a difficult airway, including demographic information, history or medical records, and physical examination findings (Table 1) [2]. Although these factors can facilitate the prediction of difficult airways, there are no ideal predictive factors available.

Among the aforementioned predictive factors, a history of difficult airways is crucial. However, the upper lip bite test, shorter horizontal distance, retrognathia, and Wilson score have been recommended as predictors (Table 2) [10]. The Wilson score is a composite scoring method that combines various evaluation techniques (Table 3) [11]. Among these, the upper lip bite test (the inability to bite the upper lip with the lower incisors) is recommended as a bedside test that healthcare providers can easily perform to predict difficult airways (Fig. 1) [10].

Upper lip bite test. The upper lip bite test, which involves instructing patients to bite their upper lip with their lower incisors, offers a classification system based on the following criteria: Class 1, the lower incisors extend beyond the vermilion border of the upper lip; Class 2, the lower incisors can bite the lip but cannot extend above the vermilion border; Class 3, the lower incisors cannot bite the upper lip at all.

Several mnemonic acronyms help recall risk factors for difficult intubation, mask ventilation, SGA placement, and surgical airway procedures (Table 4) [12].

PREPARATION FOR DIFFICULT AIRWAY MANAGEMENT

Effective preparation for difficult airway management involves the presence of a healthcare provider skilled in airway management along with another healthcare provider dedicated to monitoring the patient’s condition, including vital signs [2,8,13]. Before the initiation of airway management, all necessary equipment should be readily available within the workspace and a portable storage unit should be accessible at all times in emergency situations (Table 5). Moreover, it is essential to explain the procedure adequately and obtain consent from the patient or the responsible person before initiating airway management. Basic patient monitoring devices should be attached to assess vital signs before performing the procedure. These devices include pulse oximetry with a variable-pitch pulse tone, electrocardiography, end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring, blood pressure measurements, and heart rate measurements.

Preoxygenation

Adequate preoxygenation is crucial before initiating airway management. When sufficient preoxygenation is performed, it takes approximately 9 min for oxygen saturation to decrease to 80% [14]. Therefore, sufficient preoxygenation time is essential for patient safety during difficult airway management. Methods such as providing oxygen for 3 min through normal breathing or supplying oxygen for 1 min through vital capacity breathing can be used [15]. Even after sufficient preoxygenation, continuous oxygen administration should be maintained during airway management procedures [2].

ANTICIPATED DIFFICULT AIRWAY MANAGEMENT

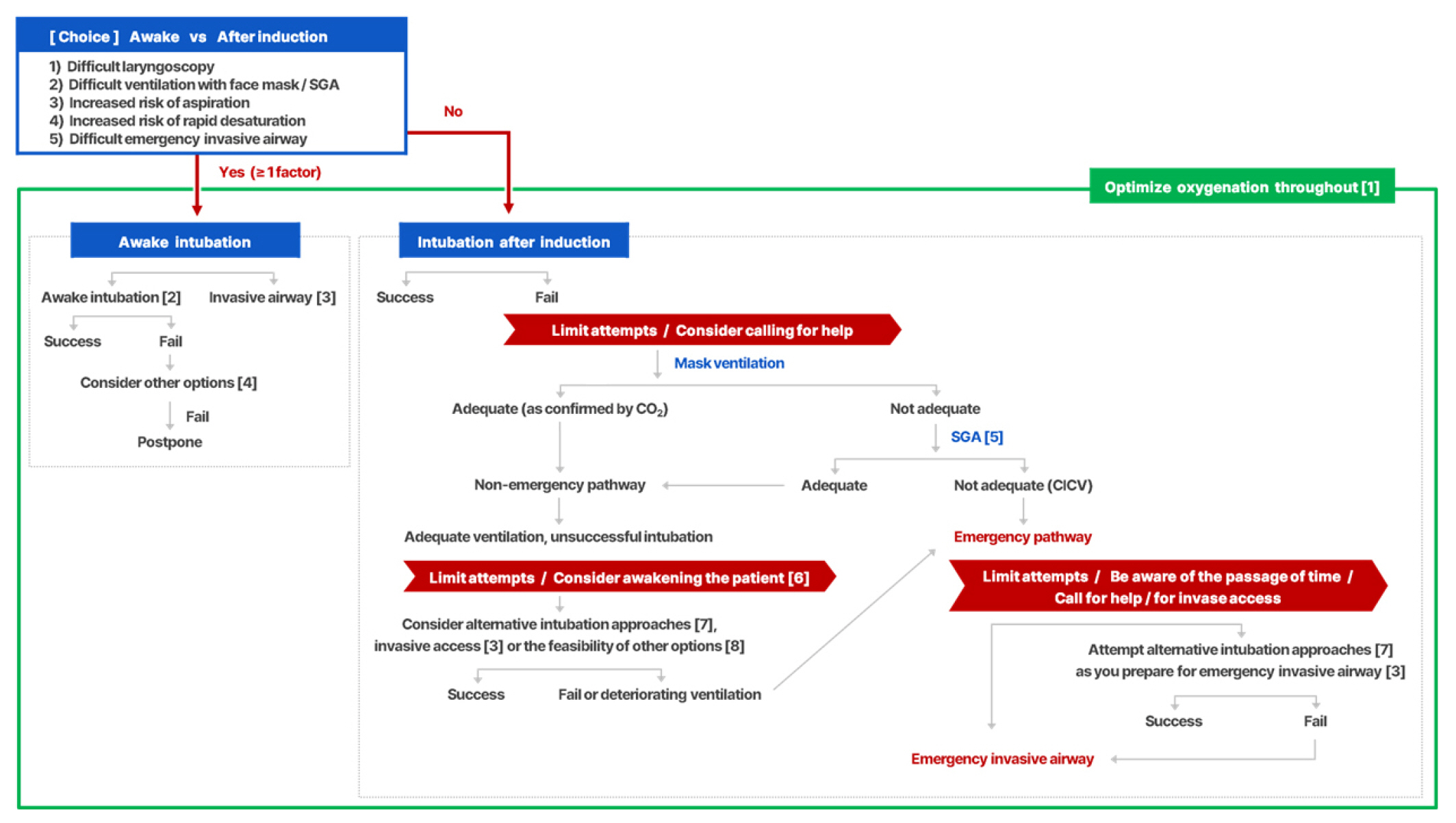

In situations where a difficult airway is anticipated, the healthcare provider performing airway management is responsible for selecting appropriate strategies and techniques (Fig. 2).

American Society of Anesthesiologists difficult airway algorithm (2022) [1]. Low- or high-flow nasal cannula, elevated position of the head throughout the procedure, and noninvasive ventilation during preoxygenation [2]. Awake intubation techniques include flexible bronchoscope, video laryngoscopy, direct laryngoscopy, combined techniques, and retrograde wire-aided intubation [3]. Invasive airway techniques include surgical cricothyrotomy, needle cricothyrotomy with a pressure-regulated device, large-bore cannula cricothyrotomy, or surgical tracheostomy. Elective invasive airway techniques include above and retrograde wire-guided intubation and percutaneous tracheostomy. Moreover, consider rigid bronchoscopy and ECMO [4]. Other options include, but are not limited to, alternative awake technique, awake elective invasive airway, alternative anesthetic techniques, induction of anesthesia (if unstable or cannot be postponed) with preparation for emergency invasive airway, and postponing the case without attempting the above options [5]. Consideration of size, design, positioning, and first versus second-generation SGA may improve the ability to ventilate [6]. Includes postponing the case or postponing the intubation and returning with appropriate resources (e.g., personnel, equipment, patient preparation, awake intubation) [7]. Alternative difficult intubation approaches include, but are not limited to video-assisted laryngoscopy, alternative laryngoscope blades, combined techniques, intubating SGA (with or without flexible bronchoscopic guidance), flexible bronchoscopy, introducer, and lighted stylet or light wand. Adjuncts that may be used during intubation attempts include tracheal tube introducers, rigid stylets, intubating stylets, or tube changers and external laryngeal manipulation [8]. Other options include, but are not limited to, proceeding with the procedure using a face mask or SGA ventilation. The pursuit of these options usually implies that ventilation will not be problematic. SGA: supraglottic airway, CO2: carbon dioxide, CICV: cannot intubation, cannot ventilation.

Awake intubation

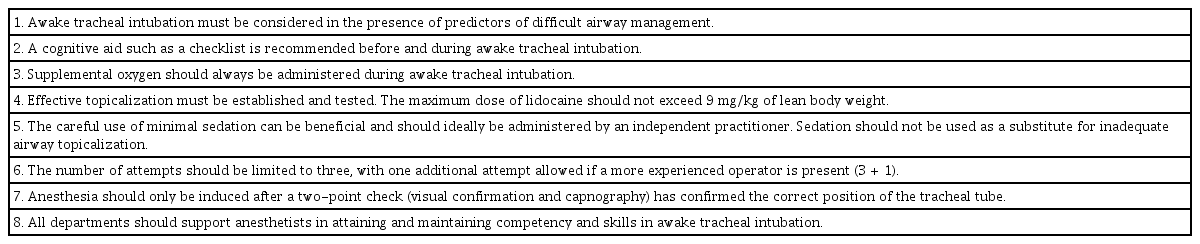

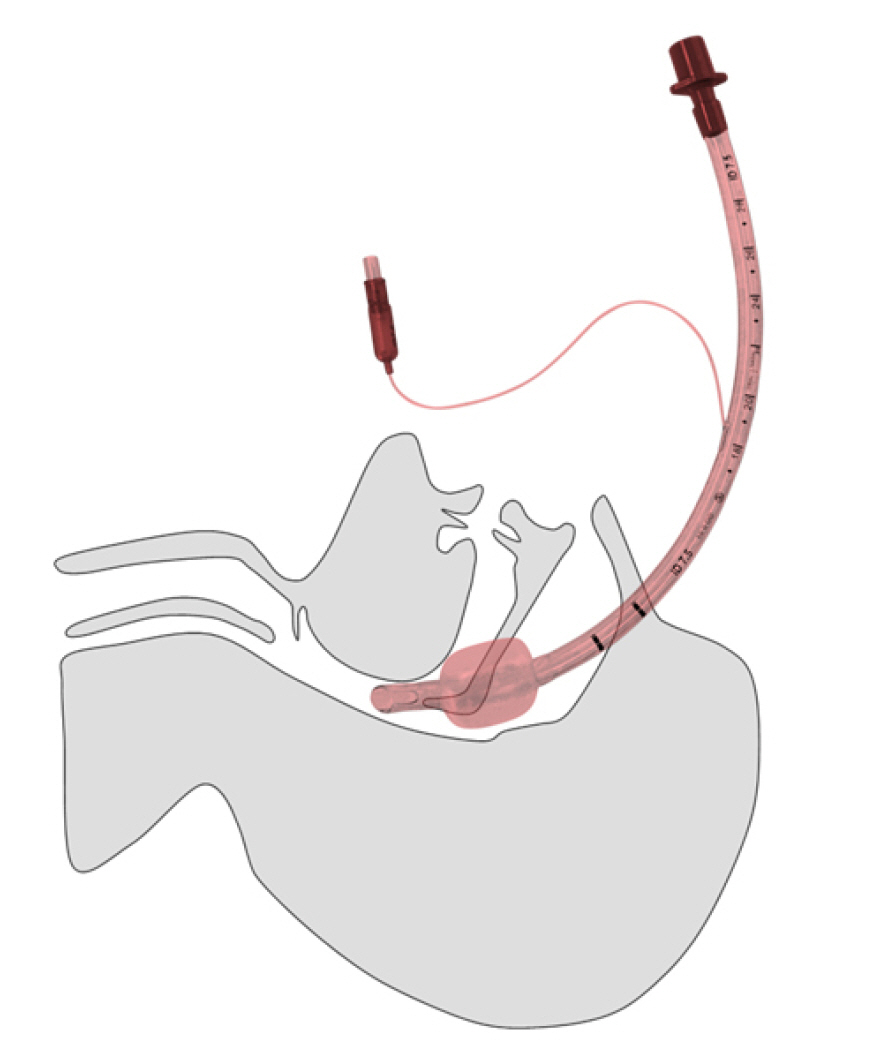

Awake intubation may be necessary for the following reasons: (1) difficult laryngoscopy, (2) difficult face mask ventilation or SGA, (3) risk of aspiration, (4) risk of rapid desaturation, or (5) difficult emergency invasive airway [2]. Methods for awake intubation include video laryngoscopy and fiber optics, as well as invasive access techniques such as tracheostomy and cricothyroidotomy [2]. Awake intubation requires patient cooperation. However, in pediatric or uncooperative patients, intubation may have to be performed after the induction of general anesthesia, regardless of the possibility of airway management challenges. In these cases, additional preparation and personnel are required. Recommendations for awake intubation are presented in Table 6 [8]. In awake intubation, the appropriate positioning of the endotracheal tube can be confirmed by visual confirmation to observe passing through the vocal cord and capnography because the tip of the endotracheal tube can be located in the oropharynx or nasopharynx while still allowing capnographic monitoring (Fig. 3). The essential factors in awake intubation are conveniently described using the acronym “sTOP” (sedation, topicalization, oxygenation, and performance). Furthermore, the characteristics of available drugs and considerations for specific situations are discussed in detail [8].

Intubation after induction of general anesthesia

1. Intubation

During intubation, it is important to perform sufficient preoxygenation and maintain oxygen supply throughout airway management. Up to three intubation attempts are allowed; additional attempts may be made if a more experienced healthcare provider is available. With each new attempt, the following variations should be introduced: (1) repositioning the patient, (2) using a video-laryngoscope, (3) changing the blade size of the laryngoscope, or (4) externally manipulating the larynx. If difficulties are anticipated, even with a new attempt, it may be appropriate to proceed to the next step without making three attempts.

2. Face mask ventilation

If intubation fails after general anesthesia induction, face mask ventilation should be attempted. Evaluation of the adequacy of face mask ventilation through end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) monitoring [2]. If adequate oxygen supply can be achieved through face mask ventilation, alternative methods can be considered: (1) awakening the patient, (2) using an SGA, or (3) using invasive access methods.

3. SGA

If the oxygen supply through face mask ventilation fails, SGA can be considered. If successful oxygenation is achieved with SGA, four options can be considered: (1) awakening the patient, (2) performing intubation through SGA, (3) proceeding with ventilation using SGA, or (4) using invasive access methods.

4. Invasive access (emergency pathway)

Invasive access should be considered when attempting oxygenation through face mask ventilation or SGA. The available options include surgical cricothyrotomy, needle cricothyrotomy with a pressure-regulated device, large-bore cannula cricothyrotomy, surgical tracheostomy, retrograde wire-guided intubation, percutaneous tracheostomy, and rigid bronchoscopy [2].

5. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)

In cases where difficult airways are expected, it may be necessary to apply ECMO before initiating airway management or prepare for ECMO before proceeding [16].

6. Declaration of failure and call for help

When the oxygen supply fails, it is crucial to declare the failure, call for help, and maintain awareness of the limited number of attempts and elapsed time. Patient awakening should be considered if feasible.

UNANTICIPATED DIFFICULT AIRWAY MANAGEMENT

When encountering an unanticipated difficult airway, it is crucial to call for assistance and optimize oxygenation. Following these initial steps, strategic decisions must be made (Fig. 4). A rapid response based on difficult airway management guidelines (including the 2022 American Society of Anesthesiologists guideline and the 2015 DAS guideline) is essential. Specifically, the following steps must be considered: (1) decide whether to awaken the patient or attempt to restore spontaneous breathing, (2) choose between noninvasive and invasive airway management, (3) consider combination techniques in noninvasive airway management, and (4) consider ECMO as an option [2].

Difficult Airway Society management of unanticipated difficult tracheal intubation (2015). SGA: supraglottic airway, SAD: supraglottic airway device, CICV: cannot intubation, cannot ventilation.

To effectively manage unanticipated difficult airway situations, consistent education and practice are essential to improve individual competencies and promote an efficient and systematic team approach through team dynamics.

CONFIRMATION OF TRACHEAL INTUBATION

Various methods can be used to confirm tracheal intubation, such as direct visualization of the vocal cords, observation of increased chest movements, and auscultation [17]. The recommended methods include capnography and EtCO2 monitoring [18-20].

In cases of uncertainty about tracheal intubation, two approaches can be considered: (1) perform extubation followed by reintubation and (2) perform a reassessment through visualization techniques such as flexible bronchoscopy, ultrasonography, or radiography [2].

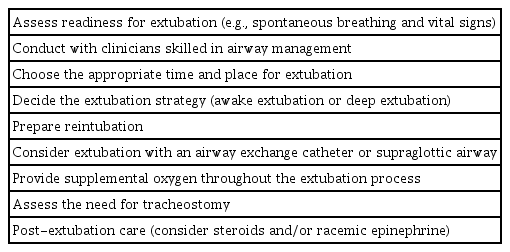

EXTUBATION OF DIFFICULT AIRWAYS

Difficulties may occur even after extubation [21]. Therefore, formalized strategies and preparations are necessary to ensure safe extubation. Consequently, the DAS extubation guidelines can be used (https://das.uk.com/guidelines/das-extubation-guidelines1) [22]. The selected strategy may vary depending on the nature of the procedure or surgery, the patient’s vital signs and condition, and the expertise and preferences of the healthcare providers. Table 7 summarizes the essential considerations that must be considered while preparing for extubation [2].

FOLLOW-UP CARE

To ensure continued safety among patients undergoing difficult airway management, information must be shared with patients or persons responsible for difficult airway management and documented. This information includes the presence of a difficult airway, the cause of the difficult airway, the solution strategies for the difficult airway, and what to tell medical personnel when performing other procedures or surgery. Additionally, patients must be registered in a difficult airway management system.

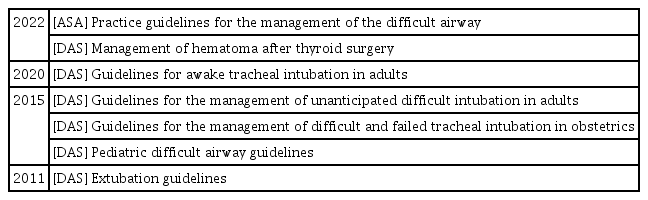

GUIDELINES

Table 8 presents the latest airway management guidelines.

CONCLUSION

It is essential to remember that difficult airway situations can occur anytime and anywhere. First, it is crucial to improve the ability of the healthcare professional to predict difficult airways. Predicting and adequately preparing patients for such situations can improve patient safety. Consequently, healthcare providers must be trained in the proficient use of airway management equipment, and it is important to ensure that the necessary equipment is readily available. Therefore, algorithms that are easily accessible for reference in such situations are recommended.

In difficult airway management situations, considerations are necessary when selecting equipment and techniques. Accordingly, it is important to develop guidelines specific to each hospital based on the experience, preferences, and capabilities of the medical team, as well as the availability of equipment.

Mastering difficult airway management goes beyond theoretical knowledge and requires practical experience. Therefore, implementing regular training through simulation-based education is the key to improving competence and improving patient safety in difficult airway scenarios.

Before initiating airway management, it is crucial to provide sufficient explanations and share algorithms with patients and their fellow medical staff. Open communication helps ensure that participants understand the plan and actively participate in the process.

Patients with difficult airways should receive detailed explanations of the causes and potential solutions before obtaining informed consent. Sharing this information in a documented format ensures that both the patient and healthcare team have a clear understanding of the challenges and proposed strategies, which fosters a sense of shared responsibility for optimal patient care.

Patient safety in difficult airway management can be facilitated through the prediction of a difficult airway, thorough preparation, simulation-based education, development of algorithms suitable for each medical site, and sufficient communication in pre-procedural explanation and post-management care.

Notes

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.